The Retinal Implant Project began in 1989 as a Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary/Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Institute of Technology collaboration. The project seeks to develop a silicon chip eye implant that can restore vision for patients suffering from Retinitis Pigmentosa and Macular Degeneration.

Age-related Macular Degeneration affects nearly 700,000 Americans yearly and is the leading cause of blindness. This central loss of vision often makes it difficult to impossible to perform detailed work such as reading. Retinitis Pigmentosa ranks number one in the world as a genetic form of blindness, denying approximately 1.2 million people sight. Peripheral vision goes flat followed by gradual loss of central or reading vision.

Blindness can result from corneal diseases, cataracts or diseases affecting the retina, optic nerve or brain. Retina diseases such as Macular Degeneration and Retinitis Pigmentosa involve only the rods and cones while cells that connect the eye to the brain remain healthy.

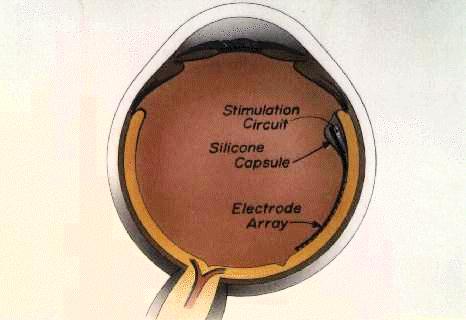

The chip under design will rest on the inside surface of the retina, opposite the damaged rods and cones and in contact with the relay cells to the brain. The use of an implant to bypass the damaged rods and cones is an approach that mirrors the way the renowned cochlear implant project has restored hearing to deaf patients. The implant will contain two silicon chips, both within the "silicone capsule." The top chip will receive light entering the eye, initially from a tiny laser affixed to a pair of glasses. A small CCD camera will also reside on the glasses to convert the visual scene to a series of laser pulses that will invisibly carry power and visual signals into the eye. The second chip, the circuit chip, will decode the laser's visual information, much as a TV set decodes the airwave signal. The visual signal will be sent to an "electrode array" that will transmit electric pulses to the eye's nerve cells.

Your support and encouragement are invaluable and make our research efforts possible. Artist's drawing of retinal implant resting on the inner surface of the retina. Light entering the eye will strike the "stimulation" circuit which will create an electrical signal that will reach the surface of the retina at the "electode array."

Joseph F. Rizzo and John Wyatt recently were invited to address cell biologists from around the world at a conference held at Copper Mountain, Colorado near Denver. The Biology/Chemistry of Vision Section of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) was held June 21 to June 25 highlighting some unique and current developments on the human vision process.

Drs. Rizzo and Wyatt presented the latest aspects of their microchip implant research to a very receptive audience. A lively and though-provoking discussion period followed their talk with many of the questions focused on the complexities of designing computer chips that must function on a relatively low power supply that will be derived form light entering the eye in contrast to the normal situation where one plugs the computer into a wall socket.

Tomorrow's Vision -We're fortunate to have attorney David Merline of the law firm of Merline & Thomas Of Greenville, S.C. helping with the legal aspects of the new foundation in Charleston. Tomorrow's Vision, The Retinal Implant Project, is our main fundraising entity and enables all gifts and donations to receive IRS "tax deductible status." Special events are being planned for the end of 1993 and the spring of 1994. If you are willing to host an event or have a fundraising idea, please contact Mary Hewlette, director of development, in Charleston, S.C. at 803-722-6338. She stands ready to assist you in any way that she can. Call her if you have an idea for an event that would be fun and especially suitable to your area or simply to say hello.

As the years go by, we'll report our progress on all fronts and continue to keep you informed of all the good things going on. You're Important to us. Feel free to write us at the following address:

Tomorrow's Vision, The Retinal Implant Project P.O. Box 21842, Charleston, SC, 29413.

To date, the project has been largely funded by private money. In particular, the scope of this project would have been greatly restricted without the support of the Seaver Institute of Los Angeles, which has generously encouraged our work since the inception of the project. We have also benefited from the good will of several other organizations and individuals, including the E. Mathilde Ziegler Foundation for the Blind and the Lions Club of Massachusetts.

The pace of our research is determined both by the skill and commitment of the individuals involved and the amount of funding available. We believe that our goal of bringing this technology to the point of human testing can be attained within three years with sufficient funding. This technology is expensive to develop but, like the rest of the computer industry, will be relatively inexpensive to manufacture. We are designing a system that will be available to anyone who is in need, regardless of economic status.

Key concerns of her area of research are the health of the retina once the implant is in place, and how well the implant is functioning. This is done through measurement using electrodes in the visual cortex of the brain. Although there is large baseline neural noise, Malini's system is sensitive enough to pick up the smaller, more delicate signals produced by the visual cortex. Malini has the ability to explain her very technical work in terms that are easy for the lay person to understand, and her enthusiasm is contagious.

Though Malini has worked in all aspects of the project, her expertise involves the development of very sensitive electronics to record electrical responses from the brain. Success here will help confirm that the implant can bridge the damaged photoreceptors, stimulate the healthy ganglion nerve cells and thereby relay signals to the brain.

Her intelligence and interest in electrical engineering come both from her heredity and her environment. Both her mother and father possess engineering backgrounds. Her father was director of electronic engineering at the India Institute of Technology, a director of Bell Laboratories and started the Bell Laboratories division in Japan when Malini was an undergraduate at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Malini shares a special relationship with her younger brother, Krishna, who was born with a speech problem. The challenge and joy of working with Krishna and sharing his success in overcoming his problem spurred her to pursue a career that involved the successful interaction of the mind and the senses. Because of her family background, Malini has traveled extensively and speaks both English and Tamil, the native Indian language, fluently. She plans to attend medical school in the Fail of '94 and upon completion of her studies, remain involved in both doing research and seeing patients. She has compassion for others and plans to donate time yearly in India helping provide health service where needed. Her goal is to make a difference and she's already well on her way.

The beauty and importance of this project generates a positive response in people. This positive response really keeps us going. Thanks for being a part of our team and dream.

Dr, Call realizes that newly emerging projects, particularly ones that are avant-garde, may have a difficult time securing traditional sources of funding. In the case of the Retinal Implant Project, Dr. Call invited a proposal from Drs. Rizzo and Wyatt, and the rest is history.

The Seaver Institute funded the Retinal Implant Project for three years, which is their traditional period of funding. After the 36 months, Dr. Rizzo was invited to California to make a presentation to the board of directors. At that time, the board indicated their happiness with the pace of the research, recognized its unusual potential and need for further funding, and agreed to support the Project for an additional year. At the end of the fourth year, Dr. Call made his yearly site visit and returned to California with the results of our research. The board chose to express their satisfaction with this research project by taking the nearly unprecedented step of funding the project for two more years.

Drs. Rizzo and Wyatt have indicated that the Retinal Implant Project would not have achieved nearly as much as it has without the Seaver Institute's support. At the time the project began, there were only three researchers to fund. The current project now has 13 members, and the need for funding has increased greatly. Drs. Rizzo and Wyatt would like to find additional funding sources to "match" the generous contribution of the Seaver Institute.